From Securing Devices to Securing Humanity: A Conversation with Adrian Ludwig

We need a new security primitive - a Proof of Human - in the digital world

Hello Cyber Builders 🖖

Few perspectives are as valuable as those shaped by decades of hands-on experience. In this exclusive conversation for Cyber Builders, I sat down with Adrian Ludwig, Chief Architect & CISO at Tools for Humanity (World ID).

Bringing over 25 years of combined experience to the table, we have both witnessed and shaped the security paradigm through every major technological shift: from the early days of hardening desktop computers and locking down perimeter networks, to the explosion of mobile computing, where Adrian led Android security at Google. Now, we turn our attention to the latest frontier: the era of artificial intelligence.

We’re entering a strange new phase of the internet — one where anyone can summon human-like content in seconds. AI can now generate faces, voices, conversations, even whole communities that look and feel real.

At the same time, we need AI more than ever: to filter misinformation, detect fraud, protect users, and scale the digital economy. But if anyone — or anything—can look human, how do we know who’s real?

That’s the question behind the proof of human (PoH) movement — and few people think about it as profoundly as Adrian, a contributor to World Network and its ambitious cryptographic infrastructure for verifying humanness online.

Laurent Hausermann: To kick off the conversation, could you give us a short introduction about yourself?

Adrian Ludwig: Sure. I am the Chief Architect at Tools for Humanity, working on the World project. I joined about two years ago as the Chief Information Security Officer to build out the security practice, hiring all the standard things you would expect. About a year ago, I transitioned into the architecture role because of many of the questions you flagged—how does decentralization work? How does privacy work? How can we possibly break this thing, which looks like a tightly coupled protocol, into pieces?

Background-wise, I’ve been doing this far longer than probably any human should! I started working in security at the National Security Agency in the late 90s, doing crypto work and early exploit development. I founded the security team at Adobe in the early 2000s, working on Flash and Dreamweaver. More recently, I ran security for Android at Google, building out the operating system from the bottom of the stack to malware detection. Before this, I was running security at Atlassian, helping large enterprises realize that running their own software stack is often a fatal flaw in their security thinking.

Laurent Hausermann: When talking to a broad audience, I often say that 25 years ago, it was about computers, networks, and engineering. Today, the digital economy has exploded, and it is about people, jobs, fraud, information, trust, and democracy. The landscape is much broader than it was 20 years ago.

Can you dive into the “why” behind what you are doing today? What kind of threats do you have in mind regarding deep fakes, synthetic agents, and these new threats popping up?

Adrian Ludwig: I’ll try a metaphor here, as I think you know enough about the security world to appreciate it. When we built computer security 30 or 40 years ago, we made a mistake that allowed buffer overflows and other bugs. The AV (Anti-Virus) industry popped up and said, “There is no integrity, so we will look for the bad things and flag them.”

It took the industry another 20 years to realize that what you actually need is a hardware root of trust for the operating system, and that operating system needs to convey trust to the applications. You need a verifiable toolchain.

That pattern—don’t build the infrastructure into the core platform, realize there is a gap, try to solve it by detection, and then realize we need to reboot and do it the right way—is exactly the same pattern the Tools for Humanity team is seeing.

We built a new digital world, but we didn’t identify humans as a defining characteristic in it. Every large software provider at scale was beginning to realize that fraud and abuse were rampant. Maybe it was “just” 5% or 8% of fraudulent users you would detect using AI and machine learning.

Generative AI is unfortunately getting so good that our current machine learning and AI detection systems just can’t keep up. It was pretty clear that our existing model wasn’t going to cut it much longer. Trying to use AI to detect other AI is a pointless exercise—a “cat and mouse” game we’re simply set up to lose.

We need a root of trust. We need the same thing the operating system vendors eventually realized: bind this to the lowest level of identity, then weave it through the rest of the protocols.

Laurent Hausermann: Great, what does it mean for the end-users? Internet consumers?

Adrian Ludwig: At a consumer level, it manifests most visibly in the erosion of social discourse. When you read comments on social media, you no longer have any confidence that you are seeing a consensus of real people. You don’t know if you are seeing a genuine debate or a manufactured reality created by thousands of bots controlled by a single entity.

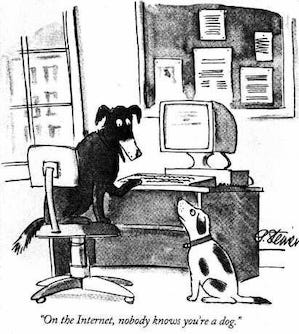

One relatable example is modern dating. There is that classic New Yorker cartoon by Peter Steiner—”On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” That used to be a joke about anonymity; now it’s a serious problem about authenticity. On a dating app, you genuinely don’t know if the “person” you are pouring your heart out to is a human being, or if it is a scammer running 10,000 accounts simultaneously using a large language model to generate romantic replies.

We have culturally accepted this as just “background noise” or a “nuisance,” like spam email. But the reality is much more pervasive. It is a fundamental failure of our digital infrastructure to answer the most basic question: Are you a person?

We’ve accepted it as an annoyance, but it is much more pervasive than we realize.

The technical underpinning is a lack of a root of trust.

You don’t know what you can trust. You don’t know if you are interacting with a real human.

Laurent Hausermann: What are the alternatives that predate Tools for Humanity’s new approaches? What are their limitations?

Adrian Ludwig: Alternatives that predate us include relying on identity systems built by a single entity—whether a single massive tech company or a single government.

These fail at a global scale. You can’t really trust a system globally if it relies solely on one government or one corporation. Not everyone in the world trusts the US government, and not everyone trusts a specific tech giant. To have a genuinely global root of trust, you cannot be dependent on a single centralized authority.

Moreover, most of the current solutions focus on “Who are you?“ (Identity) rather than “Are you a unique human?“ (Sybil attack resistance).

Most existing approaches fail at scale when it comes to uniqueness. Without checking for uniqueness, you are vulnerable to Sybil attacks—where one person controls thousands of accounts. In the era of AI, if you can’t prove unique humanness, you can’t distinguish between a real user and a bot farm.

Finally, most identity systems that predate World ID fail to respect the separation of context. They tend to blend everything.

There is a basic human expectation that “what I do over here” and “what I do over there” are separate things. That is a jarring privacy failure that people have accepted as an annoyance, but it’s actually a fundamental flaw in how those systems handle data privacy.

Laurent Hausermann: Continuing with alternatives, how do you feel about the watermarking initiatives that aim to apply digital signatures to content to re-establish a trust system?

Adrian Ludwig: I don’t think any system is “bad,” but no one has a robust system that solves all the problems. Watermarking helps indicate that a piece of content came from a specific source.

However, there are countless ways to evade it. The classic example is simply taking a picture of the picture. I think things like C2PA (Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity) are super helpful for understanding that something came from a piece of hardware and wasn’t entirely AI-generated.

It’s going to be a primitive we need.

Laurent Hausermann: How to use this primitive?

Adrian Ludwig: One way we are looking into it for World ID is doing face matching on a device. You go to an Orb, it takes a few pictures, bundles them into an encrypted package, and gives it back to you. When you use that credential to generate a proof for interaction with a relying party, we can request that it be authenticated. We can confirm that not only does the user possess the private key associated with the credential, but they also appear to be the person who went to the Orb.

On the client side, we can compare the real-life image of the person at that moment to the person who went to the Orb. That relies on client-side image acquisition, which, if you are a security purist, is terrifyingly insecure because the user controls the device. However, C2PA provides confidence that the image originated from the camera.

And now that can be combined with face authentication, then combined with the credential issued at an Orb, and then combined with World ID. So that a relying party can know the face you’re seeing right now is the same as the face that I presented to an Orb sometime in the past.

So you don’t need to know who I am. I can be private, but you can have confidence that I’m a real person, the same real person who owns this credential.

Laurent Hausermann: You mentioned several times building a “humanity root of trust” and speaking about primitives. Many comments I receive from peers looking at the World ID stack suggest that everything seems intertwined. Can you explain how it works and why it is so connected?

Adrian Ludwig: I agree with those observations. Our vision evolved over the last year after hard work on the project.

Something as simple as: Is your World ID the same as your proof of human? Two years ago, the answer would have been, “Yes.” If you ask me right now, they are totally separate things.

The proof of human is the interaction you had with the Orb, in which it checked your image and determined that you are a human. But, there is a second characteristic that is really important: unique humanness.

We blended “proof of human“ with “proof of unique human“ because Sybil detection (preventing a single person from creating multiple identities) is a fundamental part of what we are trying to establish.

Even that—are you human, and are you a unique human—are two separate things. You don’t actually need the blockchain to prove the first thing. You do need it to establish the second.

Laurent Hausermann: Great. That gives us two security primitives around humanity.

Adrian Ludwig: Yes, exactly. Separating the two enables private interactions with third parties. For some use cases, you can prove you’re a human without revealing your identity. For others, you can prove you’re a human AND unique.

We want to go even further and are actively working to pull the protocol apart. We want to recognize that there are things about the person, things the person possesses (documents, credentials, devices), and realize that the user has a complex interaction with relying parties.

We are moving toward a model of breaking who holds the user’s key. Currently, there is a single private key held on the user’s mobile device. In practice, that won’t work globally. The work done by the FIDO Alliance and WebAuthn, which allows multiple passkeys to be associated with the same account, is a much better model. That is the direction we are taking the protocol right now: decomposing how key management works so a user can authorize, de-authorize, and monitor different ways they interact with their World ID.

Laurent Hausermann: I read the “State of Crypto 2025” a16z report, and one thing that struck me was the use of crypto wallets worldwide. The countries where it is most used are Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia—everywhere but the US or Europe.

In the US or Europe, you can be unhappy with your government, but you still trust it not to fight against you. In other regions, the need for a decentralized trust system is higher. What is your view on that?

Adrian Ludwig: I am an amateur economist and amateur lawyer, far from a professional analyst of how governments work – but I tend to agree with that description.

Coming at it from a security angle, if you talk to people on a security team at a big SaaS company, they can tell you how much fraud is happening inside their system. They will tell you it’s serious – and they are all frustrated by the lack of effective tools to combat it.

In financial systems across North America and Europe, fraud experts can point to countless examples of wrongdoing. To the average consumer, this often shows up as spam or scams – especially on dating apps.

But in other regions facing high inflation or a lack of trust in the government, the utility of these tools is much higher.

One of our biggest challenges has simply been scaling globally. How do you grow from 18 million users to a billion when”proof of human” requires a physical Orb? It means deploying a large network of devices. By early next year, we plan to have at least 10,000 Orbs in the field to accelerate growth.

Laurent Hausermann: Moving to privacy concerns, I read about the German privacy authority’s concerns. There is a balance between the “right to be forgotten” and the need to prevent fraud (ensuring I cannot delete my ID just to recreate it as a new person). How do you envision addressing this?

Adrian Ludwig: It’s a balance. We encountered areas of the law that aren’t particularly well-defined, but we believe that our approach—fully anonymizing users—is the right one.

World ID doesn’t collect any data, and no one in the system has access to information that could identify a user. Our system uses AMPC (Anonymized Multi-Party Computation). With World ID Credentials, which don’t require visiting an Orb, we extract identifying characteristics from the document, anonymize them, and confirm that only one World ID can use this passport or national ID.

This allows a relying party to confirm:

This is the person holding a valid document.

They are the only ones using that document (preventing replay attacks).

Importantly, the AMPC set for this process is separate from the one used for the Orb and from the ones that might be used in the future. This decentralized approach prevents the creation of a single database containing all passports.

Laurent Hausermann: Thank you, Adrian. It is fascinating to see how the principles of security evolve from devices to networks, and now to the meaning of humanity itself.

Adrian Ludwig: Thank you, Laurent.